SCHOOL SPORTS CAN BE HAZARDOUS:

SETTLEMENT WITH KENT SCHOOL DISTRICT FOR ARM INJURY

By Jim Holland [1]

Every day millions of children are sent to schools by trusting parents in the belief that they will be safe from unreasonable risks and harms during the numerous school-sponsored activities including sports. Fortunately, most days pass with our children safe and unharmed. However, if a student does sustain an injury, the school or school district may be held accountable in damages. And parents cannot inadvertently waive those legal rights by signing an exculpatory boilerplate pre-injury release.

This action against the Kent School District (KSD) resulted in a $2,000,000 settlement, a letter of apology from the KSD and waiver of reimbursement lien for a major arm injury to a 15 year-old student athlete during wrestling practice.

School’s Legal Duty of Care: Schools have a duty to protect students in their custody from reasonably foreseeable harm. McLeod v. Grant County Sch. Dist. No. 128, 42 Wn.2d 316, 320 (1953); Travis v. Bohannon, 128 Wn. App. 231, 238 (2005); J.N. v. Bellingham Sch. Dist. No. 501, 74 Wn. App. 49, 56-57 (1994). Because the school has a special relationship with its students, it must “exercise such reasonable care as a reasonably prudent person would exercise under the same or similar circumstances.” Id. at 57. “The supervisory duty of a school extends to off-campus extra-curricular activities under the supervision of district employees such as athletic coaches.” Travis, at 238-39.

Waivers of Legal Rights Against Schools: Wagenblast v. Odessa Sch. Dist. No. 105-157-166J, 110 Wn.2d 845 (1988) holds that requiring students and their parents to sign an agreement releasing the school district from all potential future negligence claims as a condition of participating in interscholastic athletics violates public policy, and such releases are void. However, KSD argued that Wagenblast did not preclude school districts from obtaining preinjury releases from parents, whose releases it claimed were valid under , citing Scott v. Pac. W. Mt. Resort, 119 Wn.2d 484, 492 (1992). Scott is distinguishable because it applies to commercial entities such as a ski resort, which do not have the type of special relationship with students that school districts have. But KSD is a school district, like the defendant in Wagenblast. It could not escape Wagenblast through Scott.

Facts: Tyler Rothenberger’s left arm was nearly traumatically amputated on December 3, 2007, the day before his sixteenth birthday in the Kentridge High School (KHS) cafeteria during wrestling practice. Before the near-amputation, Tyler wrestled for KHS his freshman year in 2006-07, played tennis, ran track, and was a successful student. A lawsuit for damages was filed on behalf of Tyler and his parents in 2010. The case was settled for $2,000,000 in cash and an apology letter from KSD in May 2013, more than 5 years after the injury and one month before trial. The plaintiffs were represented by Ron Perey, Doug Weinmaster and Jim Holland. The defendant was ably represented by Bob Christie. The mediator, who did a masterful job, was retired King County Superior Court Judge Bruce Hilyer of Judicial Dispute Resolution.

The year before Tyler was injured, during his freshman wrestling season, wrestling practices were held in the gym at KHS.[2] After practice, the student athletes rolled up the heavy rubberized wrestling mats and often stacked them on top of one another against a solid concrete wall in the gym.

Things changed the next year during Tyler’s sophomore wrestling season, 2007-08. Before the season started, KHS Administration abruptly decided to move wrestling practice from the gym to the school cafeteria. Unlike the gym, the cafeteria contained walls of floor-to-ceiling “non-safety” glass windows.[3]

KHS Administration also appointed a new head wrestling coach. The new coach had never before served as a head high school wrestling Coach. Administration understaffed the wrestling program, and assigning the Coach to supervise more than 60 wrestlers by himself for the first hour of practice on a daily basis. While this decision flew in the face of common sense, it also violated formal KSD policy, set forth in the KSD Coaches’ Manual, requiring at least one coach for every 20 wrestlers.

KHS’s Athletic Director and Wrestling Coach then chose the most dangerous location in the cafeteria to store the heavy mats. When the mats were not in use for practice, they decided to instruct the student wrestlers to stack the mats up against a floor-to-ceiling wall of non-safety glass windows. Other safer options were readily available because there were numerous concrete walls in the cafeteria without windows. Neither the Wrestling Coach nor the Athletic Director recognized the danger of the non-safety glass windows.[4] The wrestlers (students between 14-18 years old) were required to stack and un-stack the heavy wrestling mats next to dangerous, floor-to-ceiling non-safety-glass windows without adult supervision. Participation in moving the mats was mandatory.

On December 3, 2007, Tyler’s life was changed forever. He suited up for wrestling practice and “hustled,” as previously instructed, to help some of the other wrestlers set up for practice in the new location in the cafeteria. Several wrestlers proceeded without adult supervision to the cafeteria where the mats had been stacked close against the wall of floor-to-ceiling non-safety-glass windows. Tyler took pride in setting a good example for his teammates, was eager to lead by example, and wanted to quickly get set up for practice. He was not aware of the dangers that the KHS Administration had placed before him.

Mats Stacked Against Window Wall Where Tyler Was Injured

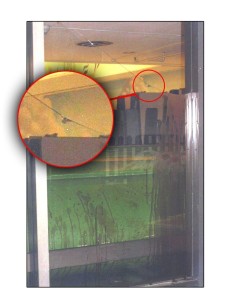

Sharp Edge of Non-Safety Glass Window That Caused the Near-Amputation With Defect In Glass and Blood On the Window and Mats.

When Tyler started to move the mats, he discovered the upper mats were stuck together. He climbed onto the stack of rolled up mats on his hands and knees as he had seen other wrestlers do in the past, so he could break the friction between the mats. His knee slipped, and he reached for the window frame (mullion) to catch himself. He missed the mullion and touched the glass instead. The upper part of the non-safety-glass window popped out, leaving a sharp edge.

Tyler’s left underarm fell onto the remaining sharp window edge with his full body weight. The untempered glass guillotined his armpit and severed all the arteries, vessels and three nerves in his arm. Tyler’s body was stuck on the sharp window shard and blood was spurting everywhere. He was lifted off of the window; a fellow wrestler and the coach applied pressure to Tyler’s arm until paramedics arrived. This likely saved Tyler’s life because he had lost a large volume of blood. Tyler was transported to Harborview Medical Center for emergency surgery and his left arm was saved. Tyler’s athletic career ended that day.

Nearly every witness in this case admitted that a solid wall was a much safer place to stack and store wrestling mats, that many solid walls were available in the cafeteria, and that Tyler would not have had his arm nearly amputated if KHS had chosen a solid, safer wall.[5] Besides being non-safety glass in the window wall, a close examination of photos of the window taken just before the accident showed a defect (chip) in the glass where it broke. Plaintiffs’ experts so testified, including wrestling and sports Expert Gary Rushing, Human Factors Expert Rick Gill, Ph.D., Architectural and Building Code and Safety Expert Mark Lawless, and Materials Expert Bob Anderson, Ph.D. Jay Syverson prepared illustrations of the injury scene and mechanism of injury. For the five years between Tyler’s injury and trial, however, KSD formally denied liability.

This near-amputation was entirely preventable. In 2002, following inspection of KHS premises, Seattle & King County Public Health Safety Inspector Patrick Murphy wrote the KHS Principal and KSD Risk Manager Keith Klug, notifying them that, among other things: “[s]afety glass must be installed in the display cases in the library and other large glass areas in the building to protect against accidental breakage.” KSD not only dismissed the recommendations, but failed to warn school administrators, coaches or the KHS school safety committee of the potential danger. There is a children’s playground immediately outside these non-safety glass windows.

Injuries & Damages: At Harborview Medical Center, Tyler underwent two surgeries to restore vascular blood flow and try to reconnect the severed nerves. The saphenous vein was cut from his left leg and grafted into his arm. He then had three more orthopedic surgeries, including cutting tendons from his foot and transferring them into his hand and wrist. Tyler’s left thumb is permanently fused. He will need at least two further surgeries, for a total of seven surgeries.

Because over 5 years had passed and the surgical wounds and scars had matured, Tyler’s arm injury was not obvious when he wore a long shirt. In order to recreate the horror and magnitude of the injury, we engaged High Impact of Colorado to create a series of graphic medical illustrations to use at trial. These were very effective at the settlement mediation.

Tyler’s treating orthopedic surgeon, Douglas Hanel, M.D., testified at his deposition that Tyler’s future surgeries –another tendon transfer (sixth surgery) and another scar revision (7th surgery) –are necessary to prevent early onset arthritis and premature degeneration of his injured arm, as Tyler lives with it for the next 54 years. Unfortunately, these surgeries will not restore any additional function. Dr. Hanel testified that Tyler’s injury is very complex, he will have daily pain for the rest of his life, he will have permanent loss of nearly all sensation in his hand and fingers for the rest of his life, he will have permanent cold and heat intolerance, and his left arm will be a “helper” hand at best for the remainder of his life. Dr. Hanel testified that had Tyler not been so young when this injury happened, he would have amputated Tyler’s arm.

Dr. Theodore Becker, Ph.D., testified at deposition about Tyler’s significant post-injury physical capacities and limitations. Plaintiffs’ consulting neurologist Dr. Marc Kirschner, M.D., testified at deposition that Tyler essentially lost half of “what makes us human,” the opposable thumb. Tyler and other lay witnesses described Tyler’s daily and hourly challenges with basic tasks such as: tying shoes, getting dressed, putting a belt on, buttoning a shirt and opening jars.

Plaintiffs’ vocational expert and life care planner Anthony Choppa testified at deposition that Tyler’s post-injury job opportunities are significantly limited given his disability. While Tyler can work, with one arm he will always be slower, and therefore less productive and competitive, than with two arms. Tyler’s injury will have real and permanent effects over the course of Tyler’s working life, which spans nearly four decades. For instance, Tyler will never be in the U.S. military service (once a desire of his), or employed flying an airplane or driving a truck. Tyler is currently employed part-time at local hotel, where he works at the front desk for minimum wage.

Economist William Brandt, C.P.A., M.B.A., calculated the present value of Tyler’s net future lost earnings and benefits from the injury (the difference between what Tyler would earn with two good arms versus what he will earn with a disability) at between $675,000 and $1,100,000. Tyler’s past medical bills were nearly $200,000. The present value of his future medical and life care costs was estimated to be about $113,000. As might be expected, KSD’s projections of economic loss were considerably less, including no lost future wages.

The greatest harm in this case is the loss of enjoyment of life and self-esteem, and the noneconomic losses associated with the near-amputation of a 15-year-old athlete’s arm. With a normal life expectancy, Tyler will live through the year 2067, spending more than 54 years largely without the effective use of his left arm. This injury will affect every aspect of Tyler’s daily life: using the bathroom, swinging a golf club, carrying his wife across the threshold, hoisting children and grandchildren onto his shoulders, protecting himself and his family from harm.

Given the severity and duration of Tyler’s injury, KSD’s willful ignorance of a serious risk, KSD’s denial of liability and their affirmative defense blaming a 15-year-old child who was required to confront a risk that an adult coach could not recognize but which KSD knew about, we argued at mediation that a jury would likely award substantial damages against the fourth-largest school district in the State, charged with protecting 27,000 children. The case did not settle at mediation on April 3, 2013, but did settle one week later with the follow-up assistance of Judge Hilyer.

Conclusion: School districts have a duty to exercise reasonable care toward students on their premises, including during athletic activities. They should heed advice from safety inspections and use common sense, a quality sorely lacking in Tyler’s case. Had KSD appreciated the danger of young bodies in motion around large glass windows, Tyler would have the full use of his left arm, a full scholastic and athletic career, and the life he should have had. This $2,000,000 settlement will again change his life and allow him to pursue his dreams with financial security.

During the intervening 5 years, no one from Kentridge High School or KSD ever contacted Tyler or his parents to express their sorrow for the preventable injury. In addition to the $2,000,000 settlement offer, the apology letter went a long way towards allowing the parties to settle the case and finally lay this matter to rest.

[1] This article was originally co-authored by Jim Holland, Ron Perey and Doug Weinmaster.

[2] Wrestling requires numerous large, heavy mats weighing approximately 400-600 pounds each to be laid out and taped together on the floor at the beginning of each practice, wiped down after practice and then rolled up and stored out of the way at the end of practice.

[3] The cafeteria was no longer code-compliant when used as a gymnasium, as it did not have safety glass. For decades, gymnasiums have required safety glass due to the foreseeable danger of human impact.

[4] Safety glass is an industry term referring to tempered glass (which breaks into pebbles rather than sharp shards), or untempered glass with a laminate layer (which will hold the shards together if broken and prevent penetration and lacerations). The KHS cafeteria windows were untempered, floor-to-ceiling windows (not safety glass of any type), the most dangerous type of glass in production.

[5] KSD admitted in briefing that: “[t]he safety solution was simple – store the mats against a wall that did not have windows.”